In view of his recent death, I remembered how Bernardo Bertolucci admitted to have shot the infamous unscripted rape scene in Last Tango in Paris with Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider, the latter being kept completely in the dark about the scene because Bertolucci wanted to capture her reaction “as a girl, not as an actress”. Schneider took to drug abuse and depression surrounding the controversy that built for several years around the film, and died in 2011. Bertolucci said he felt guilty at having done that, but at the same time, it was a depth he was willing to explore.

“I feel guilty but I do not regret. To make movies sometimes to obtain something we have to be completely free. I didn’t want Maria to act her humiliation, her rage, I wanted Maria to feel, not to act. Then she hated me for all her life.” -Bertolucci at La Cinémathèque Francaise, Paris

Bertolucci is just one among many notable names who have crossed such barriers in the name of art. That brings us to an important question that to what lengths can artists exercise their aesthetic rights for the sake of art? Is it really okay to detach basic human rights in order to create a work of art that is unparalleled? Or does the art itself have any limits? I am not qualified enough to answer this question even to myself as of yet, but the act of stripping the veil of life off the actors is indeed deplorable to me. If one attempts to create a scene that strikes the audience as original, as if they are living it at that instant, then the scene is said to be well executed and the film is “relatable”. But in this case, where the actor has no idea about the shot about to be done (let alone consent), while on the part of the director that might be maintaining ingenuity, on the part of the actor it is violation of basic human rights, and on the part of the audience who are enthralled at the “incredible acting” it might just be forced voyeurism.

Unfortunately these boundaries are not very clearly defined even after 130 years of cinema. Cinema as an art pervades into the minds of cinephiles all around the globe, regardless of any human built barriers. What goes largely unnoticed is the connection it has to the people who build it. And I don’t just mean the actors and the director, I also intend to mention the relationship that the production, the screenwriters. the cinematographer, the assistant director, the editor, the sound engineer, and every other member of the crew share with a film being built. Each of these nodes contribute in their own way in making a film what it is, and while the faces of the actors (and sometimes the director) flash to our minds while thinking of a particular film, once in a while we do need to look up all of the nodes contributing to our favorite celluloid mastery. For instance, take Christopher Doyle’s cinematography off Wong Kar Wai’s films, and most of them would lose their brilliant colorful appeal. The neon lit cityscapes, the urban melancholy, the recurring themes of isolation owe a lot to Doyle’s genius. In his contributions, he has influenced the techniques of Hong Kong second wave cinema quite distinctly. Take the camera of Kubrick in The Shining, Khavn de la Cruz’s frames in Ruined heart, Abbas Kiarostami’s script in the entire Koker trilogy, Godard’s screenplay in Pierrot le fou, take any favorite film of yours. It’s not just the actor who is the artist here. The word artist has shaped and molded itself to include the entirety of the crew who work relentlessly in creating the magic on your nearest screen.

If art is what keeps the artist alive, is it actually possible to separate the two?

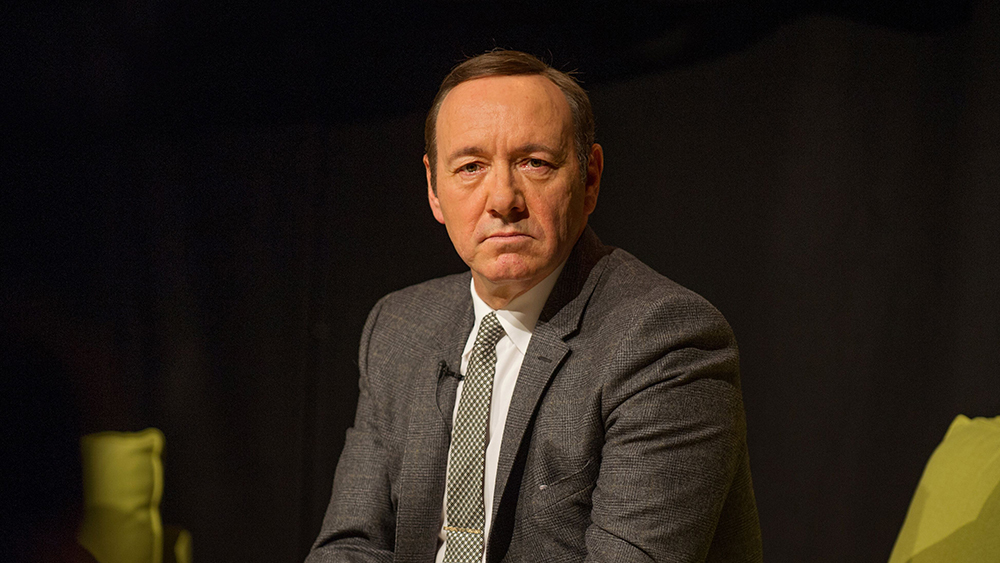

On 30th October 2017, in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein scandal, an allegation by the actor Anthony Rapp sprawled into light, claiming Kevin Spacey had sexually harassed him. Spacey tried to deny it claiming he was gay! In a matter of days, there were several other similar allegations (including alleged pedophilia) against Spacey, and his repeated denial of the facts could not save him from being jostled off the films and TV series (House of Cards, Netflix) he was shooting at that moment. The #MeToo movement just having been started around that time, it led to several people coming forward with their stories of sexual harassment on social media, from common people to actors like Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Lawrence and Uma Thurman. The movement quickly spread from America to all over the world with a large section of artists crumbling down in the face of allegations. That led us to an important question, Sure we do hate these people now for being sexual predators, but what about their work? What about the films and books and paintings and artworks they have already made? Should we dispose them off as well? Should we separate the cream of their talent from their toxic personalities? How do we as an audience, separate our ethics from our aesthetics?

The act of sexual harassment is inarguably loathsome to say the least, and it rips off all senses of humane qualities from the predator. But it is here that we might have to draw the line between part and persona. In the modern age, the sense of aesthetic is synonymous to having a distinct cultural identity. In order to answer the above questions, and to frame my own ethical idea, I have come to consider the following. The creation of an artwork is an act of breathing life into something, it is an act of birth. Thereafter, the artwork can be thought of an independent entity, bearing an influence of the creator but not fundamentally attached. In fact, artworks might be attributed to, but definitely do not account unconditionally to the artist. If as an audience we consider the intellectual identity of the film we are watching, rather than the director’s, or a certain actor or crewman’s, maybe we can discern between the aesthetic and the ethic, and consider the identity of the film as a result of the collective effort of a group of talented people, rather than the felony of one.

For example, while watching Manhattan, or Annie Hall, we have to remind ourselves that Woody Allen, the filmmaker and also the actor, was accused by his adopted daughter of sexually abusing her. Allen lost four exhaustive court battles trying to prove his alleged innocence, and was made to pay over $1 million in legal fees. Judge Elliott Wilk, the presiding judge in Allen’s custody suit against his daughter found his behavior “grossly inappropriate”. It is of no doubt that as an audience we are required to reject such a man. At the same time, both films being favorites of mine, we could focus on their themes, their treatment, their techniques rather than Allen’s personal history.

The decision to rip off power and respect from an artist lies with the production and the cohorts of people associated with practising that art to a large extent. The world sadly still being entirely patriarchal, there aren’t a lot we could be doing in order to reject an artist completely in wake of their misogyny coming to daylight. Sure, we could stop going to watch their films and reject them personally, but we need to remind ourselves of the sad truth, that a small group of people rejecting an artist would not take much away from them. There are still huge groups of “fans” who would stand by their favorite artist, provide them support instead of calling them out. A huge section of the world is blind. Unfortunately this group is so magnanimous, unless the artist’s act of hatred reaches the production or other people in power, the artist’s life would not be affected the least bit. This is exactly what can be seen when Kevin Spacey returned with his ‘Let me be frank’ video on Christmas eve, 2018. The actor is seen pleading to people to believe in his talent and fame rather than the accusations (more than 30 in number) against him, and in fact a large section of fans comment they cannot wait to see him back on screen. However what is interesting here is the role of media. Several leading news and pop culture sources have come forward asking and educating people of the gravity of the situation and why Spacey’s act needs to be seen as just an act and be rejected.

Boycotting a film would affect the production more than the actor or the director. Generally, the cast, crew and the director are paid their paychecks by the production as they complete the film. The producer henceforth leans on promotion tactics and interviews to spread the word and hype about the film, involving the actors and the director, promising them a share of the profits for promoting the film. The distributor buys the film from the producer, and it finally reaches the audience. This hierarchy is maintained if the film suffers in the market. For instance, the distributor suffers first hand in the age of piracy, the production suffers eventually and the profit margins of the actors and the director decreases. This would not affect an established director or actor much for that particular film, except that the production would think twice before investing in them henceforth. As the audience, hence we do not have much to do to cause an upheaval in an artist’s career prospect in this case, unless we can raise our voices and get them heard by that fraction of stubborn audience, and the production, and people in power who would make it easier for facts to climb up the hierarchy. The production, the distribution otherwise have no reason to oust an artist who are after all their moneymakers, unless the audience- the moneybringers coerce them to. Belief in the victim and the facts is the keyword here, and has way more power and appeal than that of schadenfreude.

Art and artists have evolved over the ages, and will continue to do so in more intricate, complex ways. What is important in their perception is subjectivity. Art appeals in very different ways to different eyes, and the experience of the viewer is a part and parcel of that form of art. This is why I find discussions over fifty greatest films of all time and similar topics very pointless. While it is frivolous to decide on superlatives without having watched everything in that temporal period, the act of claiming something as a favorite is also by definition a subjective notion. One might not appreciate a certain component of cinema as another, and our own sense of aesthetics always trickles down our opinions. The same goes for artists as well. This is the reason why after screening Lars von Trier’s The House that Jack built in Cannes 2018, half the audience walked out during the screening and the remaining gave a ten minute standing ovation at the end of the film. This also brings us to an important question, in order to like a film, does one have to necessarily agree with everything it says?

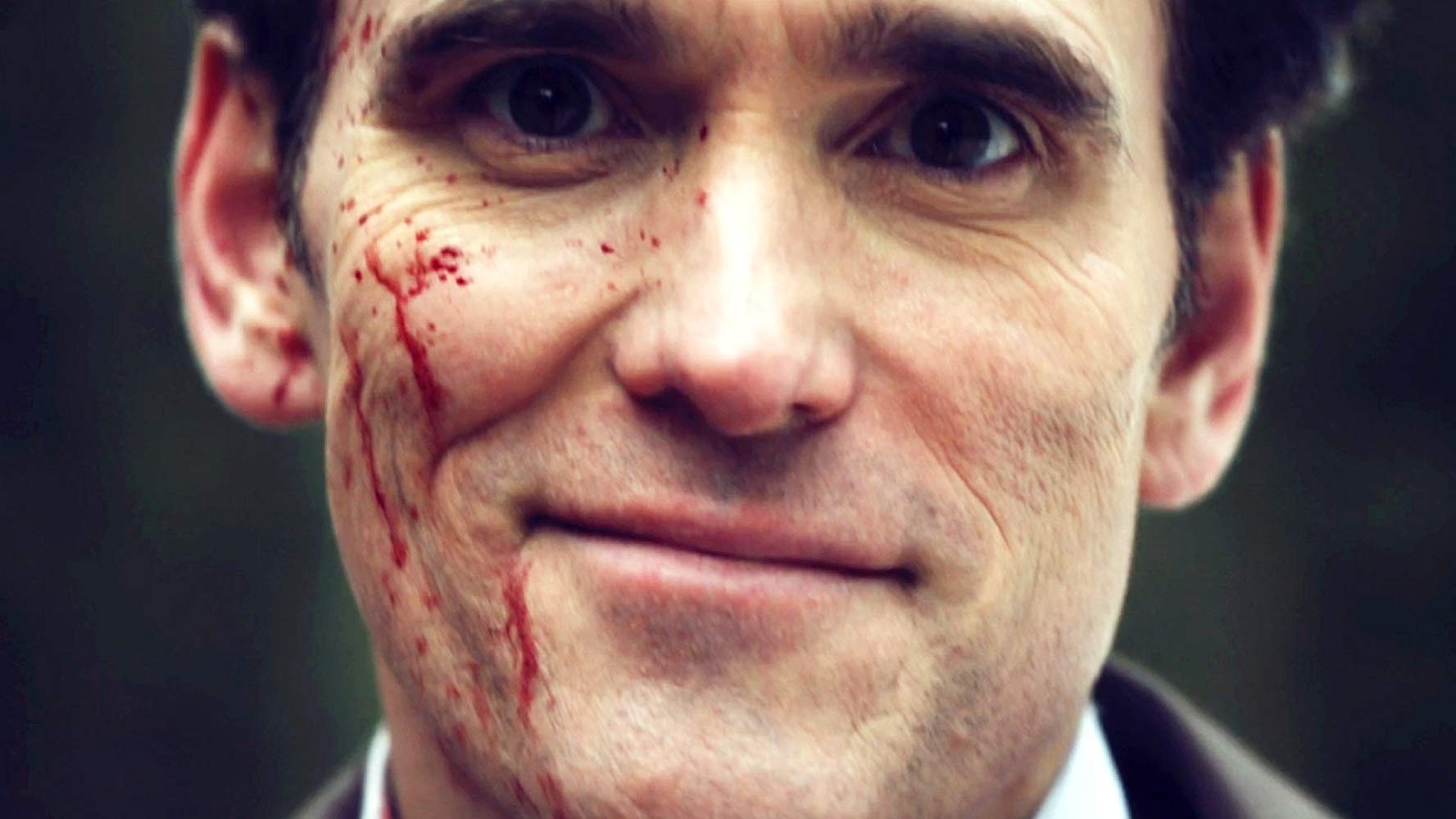

One does not. A film is a story, a carved piece of pie that represents the entirety of it, and there are several aspects to it that the director has to overlook in order to keep banality away. As the audience we might not need to agree with everything claimed by the director, and we might form an independent opinion of the film after checking the facts. But for the time when we are just the audience we can just judge a film by the feelings it evokes in us, regardless of our personal opinions and the credibility of those feelings. Drawing the previous example, in the film The House that Jack built, Matt Dilon delivers a short but severely misogynistic speech about how men are mostly the victims and women find it easy to gain sympathy. (Knowing the director’s opinions on similar issues and his denial of feminist ideals, I know LVT probably meant it when he said this film contained a part of him). I don’t agree with any of the things he says in that speech, but I still think The house that Jack Built is one of the finest films of 2018 and arguably the best of LVT’s career yet.

The relationship between an artist and their art is sacred and essentially shaped by the audience, the production and the society in general. We as the audience therefore have a conscious responsibility to uphold the freedom of expression, the artistic liberties of the artists in collective, and the power of truth. After all, art has the power to create, to destroy, to heal, to mend, and it all comes down to us to become the flagbearers of this generation, to preserve the sanctity of art and all of the strength it brings to the artist and the audience.

-Debmalya Bandyopadhyay

He can be reached here