“Rome wasn’t built in a day.”

When I was a kid, one of my chimerical longings of travelling to spellbinding whereabouts of the world included the emblematically beautiful city of Rome. It was only through rigorous high school history lessons later in my life that I came to learn about the poverty and political turmoil plaguing a traumatised Italy following World War II. Who could have thought that the once august Roman empire would wind up in such forlorn state with the passage of time?

Vittorio De Sica, the director of the reviewed film, had already bagged an Honorary Academy Award for Sciuscia (English: Shoeshine), a movie which in zeitgeist served as a precursor to Ladri di Biciclette. Back in the days of post-war destitution, De Sica sought inspiration from the happenings of the working class for his films- a movement now christened ‘neorealism’. With the cinematic tool of neorealism, he skilfully captured the negatively picturesque Rome and its citizenry in both his masterpieces. Such a perspective towards celluloid seemed ingeniously logical and pragmatic- shouldn’t the perfect mise-en-scene be real-life locations, and shouldn’t the ideal actor live the role quite literally?

Warning: Spoilers in the next paragraph

Ladri di Biciclette, one of the founding stones of Italian neorealism, has a simple yet very well-documented narrative. Antonio Ricci is an impoverished man who is driven by the need of a job to support his family. The film commences with a hopeful multitude opting for work on a regular morning in Rome which, surprisingly yet finally, happens to be a lucky one for Antonio. However, his salvation demands a prerequisite in the form of a bicycle, a trifling object which shall ironically serve as the backbone for both his livelihood and the plot of the film. This prompts his unwavering wife Maria to pawn her dowry bedsheets to redeem his pawned bicycle. The audience is then introduced to their plucky young son Bruno as he examines the bike in admiration. Antonio’s work is that of a poster-hanger; on his first day, we see him atop a ladder slapping a poster of Rita Hayworth no less, a quintessential icon of Hollywood glamor allegorically on the other side of the world as Antonio. It is at this moment when another needy young man like him snatches the stalled bike and evades the ensuing chase by a frantic Antonio. Even as a horrendous predicament such as this has befallen upon him, our rooted-for protagonist must make ends meet no matter what. His attempts to fetch back the bike escalate to greater and greater heights as the movie progresses- each to little avail. Nevertheless, Antonio and Bruno do come within an ace of clutching the thief on a couple of occasions. A particularly nonplussed scene highlighting his state of desperation involves the father-son duo slipping into a brothel in pursuit of the thief, only to be ejected out by the denizens. In the wake of such an impossible search amidst an equally bewildering Rome, a man’s hope can withstand just as much. On their way back home, Antonio momentarily halts at the sight of several unattended bicycles in the locale of a jam-packed National Football Stadium. Tempted to steal a bicycle himself, he does exactly that; albeit this act follows a famous scene of soul-searching in which Bruno is instructed by his anguished father to take the streetcar to home, lest his innocence should witness his own father commit the theft. Poor Antonio caves in to unsuccessfulness yet again, as his attempt is quickly foiled by hue and cry. Worse still, Bruno has missed the streetcar and he laments at the shocking display of his father being assaulted by bystanders. A light of compassion shimmers amid the buffeting, when the bicycle owner forgives Antonio at the immediate sight of a distressed Bruno, whose tiny hands clutched his father’s fingers in visible helplessness. The father-son duo moves away from the withering bystanders and wanes into the unassuming crowd in the closing moments of the film, with the former struggling to hold back tears.

The city of Rome has a menacing effect on the whole composition of the film. Not once does it slip our minds that the despair De Sica portrays in his work is not just of Antonio but of the city itself. Altogether we see urban streets riddled with potholes, people inhabiting crumbling houses, people pawning their possessions in vast numbers, a peddlers’ market the size of a city block, people flocking into public transportation means (much reminiscent of livestock huddling into a barn, like in the opening shot of Modern Times), and lastly as it bubbles out from my introspection, people unitedly resorting to religion for reassurance of better times. Coming from someone who has lived the majority of his life in the 21st century, the post-war hardships of the Roman working class unravel to me in the same way they do to Bruno as he travels all over the city alongside his father. In one scene, an entire constabulary rush to an important urgent meeting, leaving no policeman to attend to the contextually petty theft complaint by Antonio.

Speaking of Antonio, well, his battle with poverty is the core of the film. One might be inclined to think that Antonio is almost Chaplin-esque in the definition of his character; this is not entirely true- while Chaplin’s The Tramp had a chimerically cheerful, almost nonchalant outlook towards living on the breadline, Antonio is as gritty and real as it gets. I opine that Antonio is certainly more relatable- a man supporting his young family by all means necessary, despite his flaws and societal pressure. Relatability is indeed a timeless formula of art-making. At certain moments, however, Ladri di Biciclette does seem Chaplin-esque. Antonio can be observed to be notably careless (along the character traits of The Tramp) many-a-time throughout the movie. The scene in which he leaves his bike unattended to check on Maria while she was upstairs seeking advice from the psychic is one such example. This scene is also masterful for toying with our judgement, as the bike is still there (excellent work from De Sica for blind-spotting the bike until Antonio’s complete exit). The brothel scene mentioned earlier is also a testament to his carelessness. The ending of the film is almost a shout-out to that of Modern Times (albeit in a tragic way), while Antonio and Bruno share several light-hearted scenes evocative of The Kid.

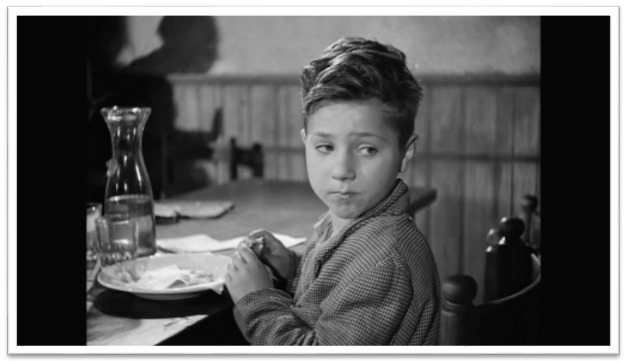

There are a couple of moments in the film which offer good cheer, stemming from despair itself, with the general cloud of destitution always looming. Almost every reviewer of this film has raved about the dining scene at the pizzeria, and rightfully so, since not only does this scene bring out the most humane side of a so-far seemingly one-dimensional Antonio, but also it interlaces hopelessness, temptation, deprivation and solitude with super dexterity through brilliant conditioning and shot-selection. Besides, this is the scene which impressions the most upon casual, first-time viewership. As previously discussed, Antonio Ricci has resonating flaws deeply-rooted in every human being. It is these flaws which bring out how much of a loving father he truly is. His wrongful admonishment of Bruno consequentially motivates him to cheer his son up by taking him to the pizzeria. Towards the end as he taps his breaking point, he realises that he cannot be a role model for his son- at best he can try to be a good father, which he does.

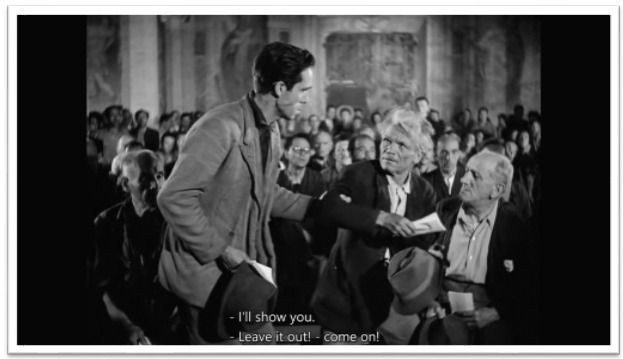

There are a few religious implications in the film which are worth delving into. Initially, Antonio pays no heed to the psychic Wise Woman; however, as times worsen he instils in himself newfound faith in her. The commotional church scene with the old man also indicates that he wasn’t ardently religious. Bruno, on the other hand, stops dead during his pursue to pay his respects to the priest in that very scene. His character has a cathartic effect on Antonio, who by nature of adulthood understands that the urban social class frowns upon people like him. Antonio is sinful since he is prone to materialism and his quest of his bicycle slowly but evidently transitions into a temptation of any bicycle. He shows no compassion even as the young lad he accuses of the theft swoons (arguably very conveniently), and even threatens to kill the old man if he isn’t compliant with his requests. Bruno is a wholesome young boy who, by curbing his longing for a fancy meal, silently accepts his family’s financial impediment in the pizzeria scene. It is the purity of his son which Antonio tries to preserve in the end, the same purity which rescues him from penal action; the same purity glistening from Bruno’s eyes, at the sight of which the father realised his immorality. In the concluding scene, Bruno isn’t inquisitive of his father’s actions at all- instead, he gives him time to contemplate.

De Sica’s remarkable urban photography becomes surprisingly more tangible upon multiple viewings of the film. For the most part, he uses wide range shots with fluid camera movements as Rome and its working class are pictured in an almost panoramic way. The panning shot toward towering shelves stuffed with people’s sheets serves as a good reminder that the Ricci family is but a speck in quotidian adversity. Even while tracking the characters, De Sica never forgets the crowd; courtesy of exquisite shot-transitions throughout the film, comparable to a maestro swiftly changing chords to produce sterling musical notes. A scene comes to mind in which a long shot of a halted Bruno by the church abruptly transitions into a close-up of his facial emotions, which might have influenced Scorsese’s filmmaking signature eras hence. The moulding father-son relation is visually captured in a very nifty way through changing shots of their respective facial close-ups. Certain shots are strangely Hitchcockian in the manner that they have a “shot within a shot” vibe to them, showcased in the suspenseful initial chase scene with the thief and in the rather histrionic church scene with the old man.

Routinely considered one of the greatest works of cinema ever produced, there didn’t seem much acclaim to Ladri di Biciclette back in the day, even though it topped the inaugural Sights and Sounds poll in 1952. It was only when the clouded sediments of post-war misery had settled down that the genius of neorealism became more apparent. The use of non-professional actors in the film, primarily Lamberto Maggiorani (who was a factory worker) as Antonio, struck a chord with cinema-enthusiasts worldwide. Ladri di Biciclette is comfortable as a time capsule rather than a social reformer, even if neorealism might be suggestive of a better financial redistribution- principally because neorealism is now looked upon as a cinema milestone and not anymore as an inspiration. This film is almost like a documentary in the sense that its powerfully simple narrative is embellished with relatable minute details of everyday affairs. In spite of being the time capsule that its legacy has built up to, the movie is paradoxically timeless in its characters that resonate with us even today. The cycle of unlawfulness, depicted in the closing sequence, is a notable theme which is recurrent in several succeeding films, for instance City of God, a movie as recent as 2002. It is said that art imitates life. Nonetheless, unlike the numerous favoured Hollywood motion pictures of its era, Ladri di Biciclette isn’t another glitzy, polished imitation of life. As Pauline Kael best puts it, “It is one of those rare works of art which seem to emerge from the welter of human experience without smoothing away the raw edges, or losing what most movies lose–the sense of confusion and accident in human affairs.”

-Avinash Dash