I remember watching Spring, summer… one summer about eight years back on UTV world movies, and getting vaguely scarred by the image of a snake swimming around a boat on which monk is setting himself on fire. Not a good first impression, I agree. But time has flown past the handrails I held closely back then, and here I am, on a re-watch schedule of everything that got me curious at that age.

I would like to consider Kim ki duk’s Spring, summer, fall, winter and spring to be a poem divided into four eponymous stanzas, each a season in the life of a monk and his apprentice. The entire film takes place on a monastery floating on a lake surrounded by a deep, quiet valley. An aged monk resides there with a young apprentice, passing their days in meditation. The monk, erudite in the ways of life, teaches the lessons he has carried in his heart for decades, to the novice who is slowly getting acquainted with the world.

Spoilers ahead

As the seasonal door of spring opens, we see this pair and a puppy living their lives in quiet solitude on the lap of nature. The apprentice as an infant, is curious about the world and puts his ideas to test fearlessly on fish, frogs and even snakes, causing them suffering in the process. The master watches over his wrongdoings, and provides him a taste of his own medicine that plunges the apprentice into guilt and remorse, with a heaviness to carry in his heart for the rest of his life.

Come summer time, and the apprentice is now an adolescent and a rooster has replaced the dog. A woman visits the monastery with her daughter who is ill, and the latter stays with the two until she gets better. In Buddhist art, a rooster symbolizes desire and craving. Naturally the apprentice having undergone sexual awakening, feels drawn to the daughter, who is about his age. She is reticent at first, but soon gives in to the boy’s feelings, and the two make love next to a waterfall. However the master soon comes to know regarding the affair blooming between the two. Instead of getting angry, he simply warns them how lust eventually brings the desire to murder. When the girl (having recovered fully) is asked to leave, the apprentice also escapes, taking the rooster and the Buddha statue along with him. Perhaps this symbolizes him leaving both with the guilt of lust and the weight of his master’s teachings.

Autumn, and the monk has grown old, the leaves have blushed. A cat has replaced the rooster, and the only thing unchanged is the solitude and silence that float over the valley like the fog of time. The monk learns about his apprentice having killed his wife and absconding. Unsurprisingly, the latter soon pays him a visit, now a grown man reeling with anger and disbelief at his late wife’s infidelity. The monk listens to his story and says that the world of men is no different than this. The apprentice, in his grief, tries to kill himself but is stopped by the monk and punished. A couple of detectives come visit the monastery to arrest the apprentice, but they are asked to wait until he completes his tasks. The next day, as he is taken away, the monk waves goodbye to the apprentice, and realizes his time in the world has drawn to an end. He sets out on his boat, lights himself on a funeral pyre, and ends the chapter of his life.

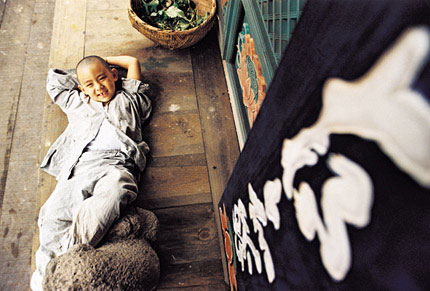

Winter, and the lake is frozen, the monastery is deserted, now only a handful of memories float atop the ashes in the master’s boat. The apprentice returns, middle aged, armed with the certainty of discipline. A snake is the animal for this chapter, it follows the events closely. The apprentice furnishes the monastery, and brings things back to normal. He finds an old book on yoga positions and starts exercising accordingly. This symbolizes him trying to break free of the guilt and sins that had gathered on his muscles over his stay in the “world of men”. Soon, he is visited by a mysterious woman whose face is covered with a cloth, and her child. At night, the woman tries to leave the child in the monastery and escape, and drowns in shallow ice in the process. The apprentice ties a weight to his waist and carries a Buddha statue up to the mountain top, reflecting upon and atoning for his sins on the way.

The wheel of time keeps rotating along the cycle of life, seasons only settle upon it’s spikes along the way. As Shelley famously wrote, “If winter comes, can spring be far behind?”. Spring returns in its full glory, with the cherry blossoms and blissful colors to the lake in the valley. The apprentice has taken the role of his late master, and the child left behind is now the apprentice. The latter’s curious outlook leads him to act similarly as his master once did when he was an infant. The entire cycle repeats, and the epilogue becomes a preface for the next chapter in the year of their lives.

The floating isolation transcending across the screen is something I find ingenious in the film. The lack of dialogues and narration is met up by visceral beauty. Special mentions to the cinematographer Baek Dong-hyeon. The camera captures the moods effectively with the seasons, and the swell of emotions that the film manages to send to the audience is something to be astonished of. This film is ki Duk’s magnum opus, from whatever I have seen from him, and has left as permanent an impact on my memory as each season has, for the two decades I have been living for.

-Debmalya Bandyopadhyay